Women comprise more than half of the people with HIV worldwide and almost 22% of persons with HIV in the United States.[1,2,3] Medical providers who care for women with HIV should be aware of the unique health care needs of this special population. This Topic Review will explore several of the most important clinical issues for cisgender women with HIV, including selection of appropriate antiretroviral therapy in women, contraception options, management of conception in serodifferent couples desiring pregnancy, gynecologic disorders, menopause, and gender-based violence. The following topics also pertain to women with HIV but are addressed in separate Lessons: (1) transgender women (HIV in Sexual and Gender Minority Populations), (2) HIV in pregnancy (Preventing Perinatal HIV Transmission), and (3) cervical and breast cancer screening (Primary Care Management). For this lesson, the use of the term women will refer to cisgender women.

- Module 6 Overview

Key Populations - 0%Lesson 1

HIV in Infants and ChildrenActivities- 0%Lesson 2

HIV in Adolescents and Young AdultsActivities- 0%Lesson 3

HIV in WomenActivities- 0%Lesson 4

HIV in Older AdultsActivities- 0%Lesson 5

HIV and CorrectionsActivities- 0%Lesson 6

HIV in Racial and Ethnic Minority PopulationsLesson 3. HIV in Women

Learning Objective Performance Indicators

- Describe key epidemiologic features of women with HIV in the United States

- Summarize contraception options and recommendations for women with HIV

- Discuss recommended antiretroviral regimens for women who may become pregnant

- Identify conception strategies for heterosexual HIV-serodifferent couples desiring pregnancy

- List appropriate steps for evaluation and management of vaginal discharge

Last Updated: February 13th, 2024Authors:Hillary K. Liss, MD,Hillary K. Liss, MD

Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine

Division of General Internal Medicine

University of WashingtonDisclosures: NoneDavid H. Spach, MDDavid H. Spach, MD

Professor of Medicine

Division of Allergy & Infectious Diseases

University of WashingtonDisclosures: NoneReviewer:Aley G. Kalapila, MD, PhDAley G. Kalapila, MD, PhD

Associate Professor of Medicine

Division of Infectious Diseases

Emory University School of Medicine

Grady Health SystemDisclosures: NoneTable of Contents- HIV in Women

- Background

- HIV Epidemiology in Women

- Antiretroviral Therapy in Women

- Contraception in Women with HIV

- Contraception Considerations for Women at Risk for HIV

- Serodifferent Couples Desiring Pregnancy

- Vaginitis in Women with HIV

- Gender-Based Violence and Women with HIV

- Menopause in Women with HIV

- Summary Points

- Citations

- Additional References

- Figures

- Tables

Background

HIV Epidemiology in Women

The following summary highlights key features of HIV epidemiology of women in the United States. These data are specifically for adult and adolescent cisgender women.

Estimated HIV Prevalence in Females with Diagnosed and Undiagnosed HIV

At year-end 2021 in the United States, an estimated 21.9% (265,900 of 1,212,400) of adults and adolescents living with HIV in the United States were female.[4] These HIV prevalence estimates include females living with diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV.[4] In 2021, an estimated 9.8% of females with HIV in the United States had undiagnosed infection.[4] For all females with HIV in 2021 in the United States, 80.0% acquired HIV through heterosexual sex and 19.4% from injection drug use (Figure 1).[4]

Estimated HIV Incidence (New HIV Infections in Females)

Females accounted for approximately 6,200 (19.3%) of the estimated 32,100 new HIV infections during the year 2021 in the United States.[4] For those women with new HIV infections in 2021, more than 80% acquired HIV through heterosexual sex (Figure 2).[4] Among the 6,200 new infections in adult and adolescent women and girls, 3,800 (61%) were Black individuals, and 1,200 (19%) were Hispanic individuals.[4]

Deaths in Women with HIV

In the United States in 2021, there were 4,743 deaths from any cause in females with HIV.[5] Although the number of deaths from AIDS-related complications in the United States is now very low, deaths from any cause in both women and men with HIV have increased in recent years, primarily due to an aging population of persons living with HIV.

Antiretroviral Therapy in Women

Indications for Antiretroviral Therapy

The Adult and Adolescent ART Guidelines recommend antiretroviral therapy for all women with HIV to improve the health of the individual woman and to decrease the risk of sexual transmission of HIV.[6] This recommendation is the same as for all other adults and adolescents with HIV.[7] Individuals who are pregnant have the additional goal of using antiretroviral therapy to prevent perinatal transmission of HIV.[6]

Gender Considerations

Available evidence suggests that virologic responses to antiretroviral therapy are comparable among cisgender women and cisgender men.[8,9,10,11] There are, however, some differences in cisgender women and cisgender men with respect to antiretroviral medication pharmacokinetics and adverse effects, which may be due to a wide range of factors such as body weight, plasma volume, and cytochrome P450 activity.[6,12,13,14] For example, postmenopausal women with HIV who are taking antiretroviral therapy have a particularly high risk of developing osteopenia and osteoporosis.[15,16,17,18] In addition, a recent pooled analysis of eight randomized clinical trials showed an increased weight gain for persons taking antiretroviral regimens containing integrase strand transfer inhibitors (specifically dolutegravir or bictegravir) and/or tenofovir alafenamide, with women having a 1.52-fold greater risk than men of developing a 10% or greater weight gain.[19] The reasons for these gender differences in weight gain are not clearly known at this time.[20,21,22]

Selecting an Antiretroviral Regimen in Women of Childbearing Age

For people of childbearing age, it is important to carefully choose an antiretroviral regimen, taking into account multiple factors, including regimen efficacy, hepatitis B status, potential pharmacokinetic interactions (with hormonal contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy), and any teratogenicity concerns about the antiretroviral medications in the event of pregnancy.[6] All instances of antiretroviral exposure during pregnancy should be reported online to the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry. For pregnant persons with HIV, the Perinatal HIV Clinical Guidelines recommend using combination antiretroviral therapy (with at least 3 drugs) to reduce the risk of HIV transmission to the child and to prevent HIV-related disease in the mother.[23,24] The use of antiretroviral medications in pregnant individuals is discussed in detail in the lesson Preventing Perinatal HIV Transmission in Module 5. The following highlights commonly used preferred antiretroviral medications in adults and adolescents that may have specific issues pertinent if an individual becomes pregnant while taking one or more of these medications.[25,26]

- Dolutegravir: Preliminary data from an observational surveillance study of birth outcomes in a cohort of pregnant women with HIV in Botswana who received dolutegravir showed a slightly higher rate of neural tube defects in infants born to pregnant women receiving dolutegravir.[27] Subsequently, two additional studies found no significant increase in prevalence rates of neural tube defects among pregnant women taking dolutegravir-containing antiretroviral regimens compared to pregnant women with HIV taking antiretroviral regimens without dolutegravir.[28] Taking into account the updated data, the Perinatal HIV Clinical Guidelines now recommend dolutegravir as a preferred regimen, both for pregnant persons (irrespective of pregnancy trimester) and for persons trying to conceive (assuming they have not previously taken cabotegravir for HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP).[24,29,30]

- Efavirenz: Previous concerns about teratogenicity associated with efavirenz have largely been quelled due to reassuring findings in several systematic reviews and meta-analyses.[31,32] A recent study of approximately 8,000 women with periconception efavirenz exposure did not demonstrate an increased rate of neural tube defects compared to infants born to women without HIV.[33] Thus, at this time, the Perinatal HIV Clinical Guidelines do not restrict the use of efavirenz in pregnancy or in people who are planning to become pregnant—efavirenz is an alternative antiretroviral drug for pregnant people and persons trying to conceive.[29,30,34]

- Cobicistat-Containing Regimens: The antiretroviral regimens that contain atazanavir-cobicistat, darunavir-cobicistat, or elvitegravir-cobicistat have been shown to have an increased risk of virologic failure in the second and third trimester of pregnancy, primarily due to lowered drug levels of these medications.[35] Thus, cobicistat-containing regimens are not recommended as initial antiretroviral therapy in people of childbearing age. If a person becomes pregnant while taking a fully suppressive antiretroviral regimen that contains cobicistat, two options exist: (1) the regimen may be continued, provided there is frequent viral load monitoring throughout the pregnancy, or (2) the regimen can be switched to a more effective and preferred regimen for use during pregnancy.[26,34]

- Darunavir: Studies have shown that darunavir levels significantly decline during pregnancy, even when given with a booster.[36,37] Hence, the dose recommendation for darunavir use in pregnancy is 600 mg twice daily given with ritonavir 100 mg twice daily. In addition, darunavir-cobicistat should not be initiated during pregnancy due to concern for lowered drug levels associated with cobicistat use.[24] If, however, a person becomes pregnant while taking a fully suppressive antiretroviral regimen that contains darunavir-cobicistat, the regimen may be continued (provided there is frequent plasma HIV RNA level monitoring throughout the pregnancy), or it can be switched to a more effective and preferred regimen for use during pregnancy.[24,34] Darunavir, boosted with ritonavir, is a preferred anchor drug for pregnant persons, regardless of trimester, and for persons trying to conceive, especially for those individuals who have a history of receiving cabotegravir for HIV PrEP.[24] If once-daily dosing of darunavir-ritonavir is used in a non-pregnant person trying to conceive, and they become pregnant, the dose should be increased to twice daily.[24]

- Oral Two-Drug Therapy: For the FDA-approved two-drug antiretroviral regimens (dolutegravir-lamivudine and dolutegravir-rilpivirine), there are limited data on use in pregnancy. Therefore, these two-drug regimens are not recommended for initiation during pregnancy, nor should they be used as first-line combination antiretrovirals in treatment-naïve individuals who are actively trying to conceive.[26] If an individual becomes pregnant while taking either dolutegravir-lamivudine or dolutegravir-rilpivirine, the clinician can consider continuing the same two-drug regimen, provided the pregnant person has undetectable HIV RNA level.[26] Alternatively, the pregnant individual can be switched to a preferred three-drug antiretroviral regimen that is recommended in pregnancy. If the decision is made to continue the same two-drug regimen, then HIV RNA levels must be monitored more frequently, typically every 1 to 2 months.[26]

- Long-Acting Injectable Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine: Data for long-acting injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine use in pregnancy are extremely limited. There are some limited safety data for persons found to be pregnant while taking injectable cabotegravir for HIV PrEP, but these individuals were all switched to full three-drug combination antiretroviral regimens once pregnancy status was verified.[38] As such, the combination long-acting injectable regimen cabotegravir and rilpivirine is not recommended as a first-line regimen for treatment-naïve pregnant individuals. For persons who become pregnant while taking long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine, expert consultation should be obtained. These persons may be switched to a preferred oral three-drug combination antiretroviral regimen, although the timing of switching will need to factor in the long half-life of the injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine.[26] Individuals who become pregnant when taking long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine and who choose to remain on the injectable therapy will need more frequent (every 1-2 months) viral load monitoring during their pregnancy.[34]

Contraception in Women with HIV

Health care providers should offer all women with HIV counseling about family planning, reproductive goals, and contraception options, and they should emphasize the importance of HIV prevention measures, including treatment as prevention, limiting the number of sex partners, correct and consistent use of condoms, and availability of HIV preexposure (PrEP) and HIV postexposure (PEP) prophylaxis for their partners, regardless of the method of contraception chosen. Discussing the risks of HIV transmission with different forms of contraception, as well as possible drug interactions with contraceptives and antiretroviral therapy, is also critical.

Guidance for Hormonal Contraceptive Use

There are a number of excellent resources for guidance related to contraception in women with HIV, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (CDC U.S. MEC), the Perinatal HIV Clinical Guidelines, and the Adult and Adolescent ART Guidelines.[6,39,40,41] These resources provide recommendations about the safety and efficacy of different methods of contraception, prescribing recommendations, drug interactions, and counseling about family planning for women with or at risk of acquiring HIV. All of these guidelines concur that women with HIV should be offered a full array of contraception choices, including hormonal options.[39,40,42] Clinicians should use shared decision-making when selecting a contraceptive method in women with HIV, taking into account the patient’s desires regarding family planning, a preferred contraceptive method, antiretroviral therapy regimen, other medications and comorbid conditions, and the risk of HIV transmission to sex partners.[39,41,42] The following summarizes the 2020 CDC U.S. MEC recommendations for the use of contraception in women with HIV:[41,42,43]

CDC U.S. MEC Categories for Classifying Contraceptive Methods

The CDC U.S. MEC uses a rating system to categorize the relative risks and benefits of each method of contraception depending on a woman’s medical comorbidities or medication use.[41]- 1 = A condition for which there is no restriction for the use of the contraceptive method.

- 2 = A condition for which the advantages of using the method generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks.

- 3 = A condition for which the theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages of using the method.

- 4 = A condition that represents an unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used.

CDC U.S. MEC Recommendations for Contraceptive Methods

- Hormonal Contraceptives: In these guidelines, hormonal contraceptives consist of combined hormonal contraceptives (including combined oral contraceptives, combined hormonal patches, and the combined vaginal ring), progestin-only pills, and implants. In women living with HIV who are not clinically well or not on antiretroviral therapy, combined hormonal contraceptives, progestin-only pills, and implants may be used without restriction (category 1). In women with HIV who are taking antiretroviral therapy, these contraceptives are considered safe, and the advantages of their use are thought to outweigh the risks. These are rated either CDC U.S. MEC category 1 or 2, depending on which antiretroviral therapy regimen the woman is using, due to concerns about drug interactions between contraceptives and some antiretroviral medications, especially protease inhibitors, pharmacologic boosters, and efavirenz.

- Progestin-Only Injectable Contraceptives: In women with HIV, progestin-only injectable contraceptives are considered safe to use without restriction (category 1). Most often, depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) is the progestin-only injectable contraceptive used. Antiretroviral medication drug interactions with DMPA are generally not clinically significant. There continues to be some evidence of a possible increased risk of HIV transmission and acquisition, but the CDC continues to recommend DMPA (without restriction) in women living with HIV. The CDC has updated its recommendations about the use of DMPA in women at high risk of acquiring HIV.

- Intrauterine devices (IUDs): Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are considered safe and effective in women with HIV, and these may be used without restriction in women who are clinically well and on antiretroviral therapy (category 1). Although IUDs are still considered reasonable options in women with HIV who are not clinically well or not on antiretroviral therapy, the U.S. MEC ranks initiation of IUDs as category 2 and continuation of IUDs previously inserted as category 1. The use of IUDs in women has not been associated with increased HIV disease progression, risk of HIV transmission, or genital viral shedding. In addition, there is no evidence to suggest increased risks of infectious complications, such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), associated with IUD use in women with HIV.[41,43] There are multiple intrauterine devices used for contraception.

Table 1. Intrauterine Devices Used for Contraception

Device Component in IUD Pregnancy Rate Year 1* Approved Duration^ Non-Hormonal Copper IUD ParaGard Copper coil 0.60-0.80% 10 years Levonorgestrel-Releasing IUDs Mirena 52 mg levonorgestrel 0.20% 5 years Liletta 52 mg levonorgestrel 0.15% 6 years Kyleena 19.5 mg levonorgestrel 0.16% 5 years Skyla 13.5 mg levonorgestrel 0.41% 3 years * These year 1 pregnancy rates are based on information provided in prescribing information

^ Approved Duration = United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved duration of useSource:- Curtis KM, Peipert JF. Long-Acting Reversible Contraception. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:461-468. [PubMed Abstract]

- Condoms: Women living with HIV using any contraceptive method other than condoms should receive counseling regarding the use of condoms to reduce the risk of transmission of sexually transmitted infections and HIV, as well as to prevent pregnancy. This is particularly important for women with HIV on antiretroviral therapy regimens that may decrease the efficacy of their contraception method.

- Spermicides: The use of spermicides containing nonoxynol-9 should be avoided in women with or at risk for HIV due to concerns about this spermicide causing genital lesions, which could lead to the increased risk of HIV transmission and acquisition. Whether used alone, with condoms, or with a diaphragm, spermicides are rated category 3 (the risks of this method are thought to outweigh the benefits) in women with HIV.[41,44]

Hormonal Contraception Interactions with Antiretroviral Medications

Since some antiretroviral medications and hormonal contraceptives are metabolized by the same enzyme pathways, drug interactions are a concern in women with HIV who are of childbearing age. The most common interactions between these classes of medications may cause compromised efficacy of the contraceptive method but, fortunately, rarely diminish the potency of the antiretroviral medications. In general, significant interactions with antiretroviral medications are more likely to occur with combined oral contraceptives and transdermal contraceptives compared with intrauterine devices (IUDs) and injectable DMPA.[39,41,45] Some of the most significant potential drug interactions between hormonal contraceptives and antiretroviral medications are highlighted below:[6,40,41]

- Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs): There are no significant drug interactions expected between NRTIs and hormonal contraceptive methods.[46]

- Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs): Among the NNRTIs, efavirenz is the most likely to interact with hormonal contraceptives. Efavirenz is metabolized by the CYP3A4 enzyme pathway and may decrease blood levels of hormonal contraceptives, leading to decreased contraceptive efficacy, including the efficacy of emergency postcoital contraception.[47] The NNRTIs doravirine, etravirine, and rilpivirine do not have this effect.[41,47,48] There are no known significant interactions between NNRTIs and DMPA or levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs.[45]

- Protease Inhibitors (PIs): Protease inhibitors undergo metabolism via the same CYP3A4 enzyme pathway as many hormonal contraceptives and can alter hormone levels.[6] Although PIs generally inhibit CYP3A4 and would therefore be expected to increase hormone levels, most ritonavir-boosted PIs actually decrease levels of ethinyl estradiol and have unpredictable effects on progestins, norethindrone, and norgestimate, potentially decreasing contraceptive efficacy.[49] No significant interactions have been identified between protease inhibitors and injectable DMPA.[45,49] When women on hormonal contraceptives take protease inhibitors in the absence of a boosting agent, levels of the estrogen and progestin components of the contraceptive may increase.

- Cobicistat: Although relatively little is known about drug interactions between hormonal contraceptives and cobicistat, this pharmacologic booster is a potent inhibitor of CYP3A and CYP2D6 hepatic enzymes and theoretically could increase contraceptive hormone levels. In addition, the effect of cobicistat on hormonal contraceptives, when used with other antiretroviral medications, is not clearly understood, and theoretically, it may actually decrease hormone levels, similar to the effect caused by ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors. The use of atazanavir-cobicistat with drospirenone-containing hormonal contraceptives is contraindicated due to potential hyperkalemia.[48] If darunavir-cobicistat is used with drospirenone-containing hormonal contraceptives, monitoring for hyperkalemia is recommended.[48]

- Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (INSTIs): The INSTIs are not substrates for CYP enzymes and thus have lower potential for drug interactions with hormonal contraceptives. Bictegravir, cabotegravir, dolutegravir, and raltegravir have both been studied with combined oral contraceptive pills, and no significant drug interactions have been identified, and no dose adjustments are needed.[50,51] When elvitegravir is given in a fixed-dose combination with cobicistat, levels of ethinyl estradiol decrease, and levels of norgestimate increase significantly; consequently, clinicians should consider using an alternative hormonal contraceptive in women taking elvitegravir in combination with cobicistat. If these medications are taken together, individuals should be counseled about possible increased risk of progestin side effects, including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, acne, and venous thrombosis.[50,51]

- CCR5 Co-Receptor Antagonists and Fusion Inhibitors: There are no significant drug interactions expected between these antiretroviral therapies and hormonal contraceptive methods.[52]

- Attachment Inhibitors: Ethinyl estradiol dosing should not exceed 30 mcg daily when administered with fostemsavir, due to increased levels of the hormonal agent when combined with fostemsavir, potentially raising the risk for thromboembolic events.[53]

Contraception Use and Risk of HIV Transmission

There are limited, high-quality data that address the potential impact of contraception on HIV transmission for women with HIV. The following summarizes the available data:

- A European study involving 563 HIV-serodifferent couples found no association between hormonal contraception and HIV transmission to the uninfected male partner.[54]

- A prospective cohort analysis in Africa that included 3,790 HIV-serodifferent couples (of which 2,476 had a female partner with HIV) found that women with HIV taking hormonal contraception (primarily injectable methods) had an approximately two-fold risk of transmitting HIV to their male partner compared with women who did not use hormonal contraception.[55] Women using injectable contraception had higher HIV levels in their endocervical secretions and this finding provided a plausible mechanism for the increased transmission risk.[55] In a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, pregnancy, unprotected sex, and plasma HIV RNA level, the investigators concluded that any hormonal contraceptive use by female partners with HIV increased the HIV acquisition risk in uninfected male partners, but the effect was statistically significant only for injectable contraceptives; the women in this study were not on antiretroviral therapy.[55]

- Several other studies have investigated the effect of hormonal contraception on HIV viral load set points, as well as cervical and vaginal HIV shedding; although some of these studies provide indirect evidence for a hormonally-mediated increase in infectivity (higher plasma RNA and higher rates of genital HIV shedding), the results have been mixed, with several studies showing no association or even an inverse association.[56,57]

- A recent systematic review of women living with HIV and using IUDs (either levonorgestrel- or copper-containing) found no difference in disease progression or genital viral shedding compared with women using other forms of contraception.[58]

Effect of Hormonal Contraception on HIV Disease Progression

Data on the impact of hormonal contraception on HIV disease progression are conflicting, as outlined below. It is important to note that most of the participants in clinical studies evaluating the effect of hormonal contraception on HIV progression were not taking antiretroviral therapy, so it remains unclear whether having a suppressed viral load on therapy would negate the potentially negative effects of hormonal contraception on HIV progression.[59]

- A study of 599 postpartum women with HIV in Zambia found that hormonal contraception was associated with more rapid disease progression, whereas the copper-containing IUD was safe and effective; secondary analysis of the data confirmed this relationship.[59,60]

- The same group studied 4,109 women at risk for HIV and found that neither implants/injectables nor oral contraceptive pills were associated with HIV disease progression.[60]

- A systematic review of 10 cohort studies and one randomized trial concluded that hormonal contraception is not associated with accelerated HIV disease progression; a variety of outcome measures were used to determine HIV progression, including mortality, onset of clinical AIDS, time to a CD4 cell count below 200 cells/mm3, CD4 count decline below a defined threshold, time to initiation of antiretroviral therapy, and increase in HIV RNA level.[61]

- A prospective study of 2,269 women with HIV similarly found no association between the use of hormonal contraception and accelerated HIV disease progression, and another small study that specifically evaluated the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) also reported the LNG-IUD does not have any adverse impact on HIV progression.[62,63]

Contraception Considerations for Women at Risk for HIV

Health care providers should offer all women at risk of acquiring HIV counseling about reproductive goals and contraception options, and they should emphasize the importance of HIV prevention measures, including treatment as prevention strategies in partners with HIV, limiting the number of sex partners, the correct and consistent use of condoms, and availability of HIV PrEP and HIV PEP, regardless of the method of contraception chosen.

Hormonal Contraception Use and Risk of HIV Acquisition

Systematic reviews of available data have concluded that no clear association exists between the use of non-injectable hormonal contraceptives, such as oral contraceptive pills, intrauterine devices, and implants, and the risk of HIV acquisition.[42,43,64,65] In contrast, several observational studies have suggested a possible increased risk of HIV acquisition with the use of the injectable progestin-only contraceptive DMPA.[55,66,67,68,69,70] Experts proposed several possible mechanisms for the observed increased risk of HIV acquisition associated with DMPA, including biologic changes (thinning of the vaginal epithelium or changes in vaginal flora), immune system changes (alteration in cytokines and antimicrobial peptides, increased inflammation, increased frequency of activated HIV target cells in the cervix, and changes in CCR5 expression), and behavioral factors (decreased condom use in the setting of reliable contraception).[42,68,71,72] Other studies, however, have contradicted concerns of DMPA and enhanced HIV risk acquisition, and several recent systematic reviews found no increased risk of HIV acquisition with the non-DMPA injectable progestin norethisterone enanthate (NET-EN).[66,73,74,75] The results of a randomized, open-label trial of intramuscular DMPA, copper IUDs, and levonorgestrel implants were published in 2019; this study, which enrolled approximately 7,800 women seronegative for HIV across multiple sites in 4 African countries, did not find any of these contraception methods to be associated with a higher rate of HIV acquisition.[76]

U.S. MEC Guidance for Hormonal Contraception in Women at Risk for HIV

In April 2020, the CDC released an update to the U.S. MEC guidance pertaining to the use of hormonal contraception in women at high risk of acquiring HIV.[39,43] After a careful review of the current data and the updated World Health Organization (WHO) MEC guidance from 2019, the CDC decided to adopt the updated WHO guidance, which is summarized below and in the table.[43,77]

Table 2. Guidance for Contraceptive Use in Women at High Risk for HIV

Copper-Containing IUD* LNG-IUD Implants DMPA POP CHCs Initiation Continuation Initiation Continuation 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 *Clarification with IUDs: Many women at high risk for HIV are also at risk for other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). For these women, refer to the recommendations in the “U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use” for women with other factors related to STDs and the “U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use” on STD screening before IUD insertion. Evidence (IUDs): High-quality evidence from one randomized clinical trial, along with low-quality evidence from two observational studies, suggested no increased risk for HIV acquisition with Cu-IUD use.§ No studies were identified for LNG-IUDs.¶

Evidence (implants, DMPA, POP): High-quality evidence from one randomized clinical trial observed no statistically significant differences in HIV acquisition between DMPA-IM versus Cu-IUD, DMPA-IM versus LNG implant, and Cu-IUD versus LNG implant.¶,** Of the low-to-moderate-quality evidence from 14 observational studies, some studies suggested a possible increased risk for HIV with progestin-only injectable use, which was most likely due to unmeasured confounding.¶ Low-quality evidence from 3 observational studies did not suggest an increased HIV risk for implant users.¶ No studies of sufficient quality were identified for POPs.¶

Evidence (CHCs): Low-to-moderate-quality evidence from 11 observational studies suggested no association between COC use (it was assumed that studies that did not specify oral contraceptive type examined mostly, if not exclusively, COC use) and HIV acquisition.¶ No studies of patch, ring, or combined injectable contraception were identified.¶

Abbreviations: IUD= intrauterine device; LNG-IUD = levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device; DMPA = depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (injectable); POP = progestin-only pill; CHC = combined hormonal contraceptive

*Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, Berry-Bibee E, Horton LG, Zapata LB, et al. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No. RR-3).†Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No. RR-4).

§ Hannaford PC, Ti A, Chipato T, Curtis KM. Copper intrauterine device use and HIV acquisition in women: a systematic review. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2020;46:17–25.¶ Curtis KM, Hannaford PC, Rodriguez MI, Chipato T, Steyn PS, Kiarie JN. Hormonal contraception and HIV acquisition among women: an updated systematic review. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2020;46:8–16.

** Evidence for Contraceptive Options and HIV Outcomes (ECHO) Trial Consortium. HIV incidence among women using intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, a copper intrauterine device, or a levonorgestrel implant for contraception: a randomized, multicentre, open-label trial. Lancet 2019;394:303–13.

Summary of Categories for classifying contraceptives

1 = A condition for which there is no restriction for the use of the contraceptive method.

2 = A condition for which the advantages of using the method generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks.

3 = A condition for which the theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages of using the method.

4 = A condition that represents an unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used.

Source:- Tepper NK, Curtis KM, Cox S, Whiteman MK. Update to U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016: Updated Recommendations for the Use of Contraception Among Women at High Risk for HIV Infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:405-10. [PubMed Abstract]

- All hormonal contraceptive options should be available to women at high risk of acquiring HIV.

- Despite conflicting data about an increased risk of HIV acquisition in women using progestin-only injectable contraception (including DMPA), the advantages of these methods outweigh theoretical or proven risks, and progestin-only injectable contraception may be initiated or continued without restriction in women at high risk for HIV without restriction (category 1).

- Women considering progestin-only injectable contraception should be counseled about the concerns of increased risk of HIV acquisition in women while using this method, the unclear causal relationship, and strategies to minimize the risk of HIV infection.

- There are no restrictions for the use of other hormonal contraceptive methods (including combined hormonal methods, implants, and progestin-only pills) in women at high risk of acquiring HIV (category 1).

- IUD use (both initiation and continuation) is rated category 1 in women at risk for HIV.

- Finally, spermicides containing nonoxynol-9 should not be used in women with or at risk of acquiring HIV due to concerns about this spermicide causing genital lesions, which could lead to increased risk of transmission and acquisition of HIV. Whether used alone, with condoms, or with a diaphragm, spermicides are rated category 4 (unacceptable health risk) in women at risk of acquiring HIV.

Serodifferent Couples Desiring Pregnancy

General Recommendations

Serodifferent couples who wish to conceive a child should first ensure the partner with HIV achieves sustained virologic suppression (two plasma HIV RNA levels below the limit of detection at least 3 months apart).[40] Once sustained virologic suppression has been achieved in the person with HIV, the serodifferent couple can have condomless sexual intercourse in attempts for conception with effectively no risk of HIV transmission.[40] Both partners should undergo screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections prior to attempting conception.[40] Several studies, as highlighted below, have shown a lack of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples if the partners with HIV were taking antiretroviral therapy and had stably suppressed HIV RNA levels.[40]

- HPTN 052: The HPTN-052 trial was a randomized, controlled study that enrolled 1,763 HIV serodifferent, predominantly heterosexual couples from 9 countries.[78,79] All persons with HIV had a CD4 count of 350 to 550 cells/mm3 at enrollment, and none had HIV-related symptoms.[78,79] All new HIV infections were analyzed phylogenetically, and during the trial no linked HIV infections occurred between partners when the partner with HIV was taking antiretroviral therapy and had stably suppressed HIV RNA levels.[78,79]

- Partner-1 Study: In the first phase of the European PARTNER (Partners of People on ART—A New Evaluation of the Risks) study, investigators at 75 sites in 14 European countries evaluated the impact of antiretroviral therapy on HIV transmission risk in 888 HIV-serodifferent couples engaging in condomless sex, including 548 heterosexual couples. The eligibility for enrollment required the partner with HIV to be taking antiretroviral therapy and have an HIV RNA level of less than 200 copies/mL. During the trial, there were zero phylogenetically linked HIV transmissions that occurred in these couples, with an estimated 58,000 condomless sex acts, including an estimated 36,000 in heterosexual couples. There were 11 new HIV infections during the study period, but none of these were phylogenetically linked.

- Natural Conception Study: In this prospective study, investigators evaluated the risk of HIV transmission among 161 HIV-serodifferent couples who were attempting conception.[80] Enrollment required the partner with HIV to have received suppressive antiretroviral therapy for at least 6 months prior to entering the study.[80] Among the 161 serodifferent couples enrolled, 133 (83%) had a male partner with HIV, and 28 (17%) had a female partner with HIV.[80] During the study, there were a total of 144 natural pregnancies, 107 babies born, and no cases of sexual HIV transmission occurred.[80]

Female Partner with HIV

When an HIV-serodifferent couple wishes to conceive and the female partner has HIV, the main prevention strategy is to have the woman achieve virologic suppression—defined as two plasma HIV RNA measurements below the limit of detection—before attempting conception.[40] Another option is to have the man take HIV PrEP (as outlined below). In addition, the risk of female-to-male HIV transmission can be eliminated, regardless of the woman’s HIV RNA level, if the couple utilizes impregnation techniques without having condomless intercourse.[40] A common impregnation method is to perform periovulatory artificial insemination, either by self-insemination with the partner’s semen, such as with a plastic (needleless) syringe, or with the assistance of a medical professional using intrauterine insemination.[40] In vitro fertilization is considered another very safe option, but it is cost-prohibitive for many couples and not usually necessary unless fertility problems exist. If the couple changes their plan and elects to try to conceive via unprotected sexual intercourse, they should be advised only to proceed after the woman has attained suppressed plasma HIV RNA levels on antiretroviral therapy for at least 3 months.[40]

Male Partner with HIV

When an HIV-serodifferent couple wishes to conceive and the male partner has HIV, the main prevention strategy is to have the man achieve sustained virologic suppression—defined as two plasma HIV RNA measurements below the limits of detection at least 3 months apart—before attempting conception.[40] Another option is to have the woman take HIV PrEP (as outlined below). Additional options to consider include using donated sperm from another man who does not have HIV, or the use of sperm preparation techniques (e.g., sperm washing), coupled with either intrauterine insemination or in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection.[40] Unfortunately, many of the assisted reproductive technology services, such as using donor sperm or surrogacy, while viable options for conception, may not be feasible due to prohibitive costs or lack of access to sperm washing. Given the extraordinary effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy in preventing sexual HIV transmission, the importance of sperm washing and other reproductive technology methods in HIV-serodifferent couples has diminished. If the female partner of a man living with HIV becomes pregnant, she should undergo HIV testing and close monitoring during the pregnancy.

Periconception HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

In certain circumstances, the use of HIV PrEP in HIV-serodifferent couples may be warranted in couples attempting conception.[40,81,82] Limited data exist regarding the efficacy and optimal use of HIV PrEP in HIV-serodifferent couples planning pregnancy. The use of HIV PrEP would be appropriate for the HIV-seronegative person in the HIV-serodifferent couple attempting conception if any of the following exist: the partner with HIV had not achieved suppressed HIV RNA levels for at least 3 months, the partner’s plasma HIV RNA level is not known, there are concerns about the partner’s adherence with antiretroviral therapy during the periconception period, and/or the HIV seronegative partner prefers to take HIV PrEP.[40] There are some data regarding pregnancy outcomes for women receiving tenofovir DF-emtricitabine-containing HIV PrEP who become pregnant. In several large randomized HIV PrEP trials, tenofovir DF-emtricitabine HIV PrEP regimens were promptly stopped if the woman in the trial became pregnant.[83,84] A subanalysis of the data from the Partners PrEP Study (conducted at multiple sites in Kenya and Uganda) showed no significant differences in pregnancy incidence, birth outcomes, or infant growth among women who were taking tenofovir DF-emtricitabine-containing HIV PrEP at the time of conception.[83,84] If periconception HIV PrEP is used as the primary prevention strategy, the partner without HIV should initiate HIV PrEP one month before conception is attempted and continue for as long as indicated.[85,86,87] The use of tenofovir alafenamide-emtricitabine is not recommended for HIV PrEP to prevent vaginal acquisition of HIV, and there are inadequate data on the use of cabotegravir in pregnancy.

Vaginitis in Women with HIV

Although most cisgender women will experience at least one episode of vaginitis in their lifetime, women with HIV develop vaginal infections more commonly than women without HIV.[88] These infections can influence susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections and increase the risk of HIV transmission to partners who do not have HIV. Three of the most common vaginal infections that occur in women with HIV are addressed in this section: bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and trichomoniasis. A more comprehensive discussion of female genitourinary infections, including sexually transmitted infections, is available in the 2021 STI Treatment Guidelines.[88]

Bacterial Vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis is a condition in which the predominant vaginal hydrogen peroxide-producing Lactobacillus species are overgrown with abundant anaerobic bacteria. Women with bacterial vaginosis may be asymptomatic, or they may develop vaginal discharge with a characteristic fishy (amine) odor. Bacterial vaginosis tends to occur (and recur) more frequently in women with HIV infection compared with women who do not have HIV; bacterial vaginosis increases the risk of acquiring other sexually transmitted diseases, and it can also increase the risk of HIV transmission to partners without HIV.[89,90,91]

- Diagnosis: The gold standard for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is a Gram’s stain of the vaginal discharge, which reveals a low concentration of lactobacilli, with multiple gram-negative and gram-variable rods and cocci. In clinical practice, however, the Amsel criteria, point-of-care assays, and nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are now more often used to diagnose bacterial vaginosis. The Amsel Diagnostic Criteria requires three of the following are met: (1) homogenous thin discharge coating the vaginal walls, (2) vaginal epithelial cells studded with adherent coccobacilli on microscopy (clue cells), (3) vaginal pH greater than 4.5, and (4) a fishy (amine) odor to the vaginal discharge that occurs when adding 10% potassium hydroxide (positive whiff test).[91] The recommended point-of-care assays include the OSOM BVBlue test, Affirm VPIII, and FemExam Test Card.[91] Recommended NAATs include the BD MAX Vaginal Panel (real-time polymerase chain reaction [PCR] assay) and the Aptima BV Test.[91]

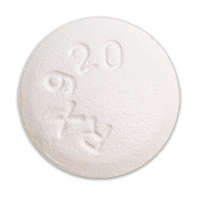

- Treatment: The treatment of bacterial vaginosis for women with HIV is the same as for women without HIV. There are three recommended treatment options for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis in nonpregnant persons: (1) metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days, (2) metronidazole gel 0.75% applied in one full applicator (5 g) intravaginally once a day for 5 days, or (3) clindamycin cream 2% applied in one full applicator (5 g) intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days.[91] Alternative regimens include the use of oral clindamycin, intravaginal clindamycin ovules, oral secnidazole, and oral tinidazole.[91] Secnidazole is a new nitroimidazole antibiotic, approved by the FDA in September 2017, for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis based on data from randomized controlled trials that found it was well-tolerated, superior to placebo, and at least as effective as multiday metronidazole.[92,93] Courtesy of National STD Curriculum.2021 STI Treatment Guidelines: Bacterial VaginosisTable 3. Treatment of Bacterial VaginosisRecommended RegimensMetronidazole500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days

Metronidazole

Tradename:FlagylRecommended RegimensMetronidazole gel 0.75%one full applicator (5 g) intravaginally, once a day for 5 daysMetronidazole gel 0.75%

Tradename:Recommended RegimensClindamycin vaginal cream 2%one full applicator (5 g) intravaginally at bedtime for 7 daysClindamycin vaginal cream 2%

Tradename:Cleocin vaginal creamNote: Clindamycin cream is oil based and might weaken latex condoms and diaphragms for 5 days after use.Alternative RegimensClindamycin300 mg orally twice daily for 7 daysClindamycin

Tradename:CleocinAlternative RegimensClindamycin ovules100 mg intravaginally once at bedtime for 3 daysClindamycin ovules

Tradename:Note: Clindamycin ovules use an oleaginous base that might weaken latex or rubber products (e.g. condoms and diaphragms). Use of such products within 72 hours after treatment with clindamycin ovules is not recommended.Alternative RegimensSecnidazole2 g oral granules in a single doseSecnidazole

Tradename:SolosecNote: Oral granules should be sprinkled onto unsweetened applesauce, yogurt, or pudding before ingestion. A glass of water can be taken after administration to aid in swallowing.Alternative RegimensTinidazole2 g orally once daily for 2 daysTinidazole

Tradename:TindamaxAlternative RegimensTinidazole1 g orally once daily for 5 daysTinidazole

Tradename:TindamaxSource: Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Diseases characterized by vaginal itching, burning, irritation, odor or discharge: bacterial vaginosis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70(No. RR-4):1-187. [2021 STI Treatment Guidelines]

Trichomoniasis

Trichomoniasis is a common sexually transmitted infection in the United States caused by a protozoan pathogen, Trichomonas vaginalis, and some studies have found that more than half of women with HIV are coinfected with T. vaginalis at some point in their lives.[94] In women living with HIV, T. vaginalis infection increases the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease, and it increases shedding of HIV from the genital tract, which may increase the risk of HIV transmission.[94] Among sexually active women without HIV, T. vaginalis infection is also an independent risk factor for acquiring HIV.[94] A randomized clinical trial found that single-dose therapy with metronidazole 2 g orally was less effective than the 7-day metronidazole regimen for women with HIV and trichomoniasis: follow-up positive trichomonas tests were higher in the group receiving single dose metronidazole.(Figure 3).[95]

- Diagnosis: Women with trichomoniasis may present with malodorous, yellow-green vaginal discharge, vulvar irritation, or they may be asymptomatic. The use of nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) in vaginal, endocervical, or urine specimens has become the gold standard for diagnosing trichomoniasis in women, replacing the wet mount preparation and culture for this purpose when available.[94]

- Treatment: The preferred treatment option for trichomoniasis in women with HIV is metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days; the alternative treatment for women is tinidazole 2 g orally in a single dose.[94] Courtesy of National STD Curriculum.2021 STI Treatment Guidelines: TrichomoniasisTable 4. Treatment of TrichomoniasisRecommended Regimen for WomenMetronidazole500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days

Metronidazole

Tradename:FlagylRecommended Regimen for MenMetronidazole2 g orally in a single doseMetronidazole

Tradename:FlagylAlternative Regimen for Women and MenTinidazole2 g orally in a single doseTinidazole

Tradename:TindamaxSource: Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Diseases characterized by vaginal itching, burning, irritation, odor or discharge: trichomoniasis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70(No. RR-4):1-187. [2021 STI Treatment Guidelines]

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is a common problem among women with HIV, occurring more frequently in this population than in women without HIV.[96,97] Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis may be the initial clinical presentation in women with HIV; with more advanced HIV disease, vulvovaginal candidiasis is often more severe and may recur more frequently.[96,98] Vulvovaginal candidiasis can impact the vaginal epithelium and increase susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. In addition, women with HIV and vulvovaginal candidiasis have higher concentrations of HIV in genital fluids; it is not clear, however, if treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis alters the risk of HIV acquisition or transmission.[96]

- Diagnosis: Women with early stages of HIV usually have manifestations of vulvovaginal candidiasis that are similar to women without HIV, namely mucosal burning and itching with evidence of white adherent plaques.[98] The diagnosis is confirmed by examining a wet mount of vaginal secretions and finding hyphal forms after applying 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH).[96] In the absence of other causes of vaginitis, such as bacterial vaginosis or trichomoniasis, a woman with candida infection should have a normal vaginal fluid pH (less than 4.5).[96] Vaginal fungal culture can be used to make a diagnosis in women with symptoms consistent with vulvovaginal candidiasis who have a negative wet mount.[96]

- Treatment: The preferred treatment options for vulvovaginal candidiasis in nonpregnant women consist of single-dose fluconazole 150 mg orally or short-course topical azoles.[96,98] Topical antifungal therapy should be used instead of fluconazole to treat vulvovaginal candidiasis in pregnant persons with HIV.[98] If topical therapies are chosen, it is especially important to counsel women with HIV that the available creams and suppositories are oil-based and might weaken latex condoms. For women with frequent or severe recurrences of vulvovaginal candidiasis, some experts recommend using a long treatment course (e.g., oral fluconazole 100 mg, 150 mg, or 200 mg orally every third day for a total of 3 doses), followed by a maintenance regimen of fluconazole 100 mg, 150 mg, or 200 mg weekly for 6 months.[96] Courtesy of National STD Curriculum.2021 STI Treatment Guidelines: Vulvovaginal CandidiasisTable 5. Treatment of Uncomplicated Vulvovaginal CandidiasisRecommended Regimens: Over-the-Counter Intravaginal AgentsClotrimazole 1% cream5 g intravaginally daily for 7–14 days

Clotrimazole 1% cream

Tradename:Recommended Regimens: Over-the-Counter Intravaginal AgentsClotrimazole 2% cream5 g intravaginally daily for 3 daysClotrimazole 2% cream

Tradename:Recommended Regimens: Over-the-Counter Intravaginal AgentsMiconazole 2% cream5 g intravaginally daily for 7 daysMiconazole 2% cream

Tradename:MonistatRecommended Regimens: Over-the-Counter Intravaginal AgentsMiconazole 4% cream5 g intravaginally daily for 3 daysMiconazole 4% cream

Tradename:Recommended Regimens: Over-the-Counter Intravaginal AgentsMiconazole 100 mg vaginal supositoryone suppository daily for 7 daysMiconazole 100 mg vaginal supository

Tradename:Monistat 7Recommended Regimens: Over-the-Counter Intravaginal AgentsMiconazole 200 mg vaginal suppositoryone suppository daily for 3 daysMiconazole 200 mg vaginal suppository

Tradename:Monistat 3Recommended Regimens: Over-the-Counter Intravaginal AgentsMiconazole 1,200 mg vaginal suppositoryone suppository for 1 dayMiconazole 1,200 mg vaginal suppository

Tradename:Monistat 1Recommended Regimens: Over-the-Counter Intravaginal AgentsTioconazole 6.5% ointment5 g intravaginally in a single applicationTioconazole 6.5% ointment

Tradename:Vagistat-1Recommended Regimens: Prescription Intravaginal AgentsButoconazole 2% cream (single dose bioadhesive product)5 g intravaginally in a single applicationButoconazole 2% cream (single dose bioadhesive product)

Tradename:GynazoleRecommended Regimens: Prescription Intravaginal AgentsTerconazole 0.4% cream5 g intravaginally daily for 7 daysTerconazole 0.4% cream

Tradename:Terazol 7Recommended Regimens: Prescription Intravaginal AgentsTerconazole 0.8% cream5 g intravaginally daily for 3 daysTerconazole 0.8% cream

Tradename:Terazol 3Recommended Regimens: Prescription Intravaginal AgentsTerconazole 80 mg vaginal suppositoryone suppository daily for 3 daysTerconazole 80 mg vaginal suppository

Tradename:Terazol 3 SuppositoryRecommended Regimen: Oral AgentFluconazole150 mg orally in a single doseFluconazole

Tradename:DiflucanNote: the creams and suppositories in these regimens are oil based and might weaken latex condoms and diaphragms. Patients should refer to condom product labeling for further information.Source: Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Diseases characterized by vaginal itching, burning, irritation, odor or discharge: vulvovaginal candidiasis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70(No. RR-4):1-187. [2021 STI Treatment Guidelines] - Prophylaxis: Long-term prophylactic fluconazole in nonpregnant women can reduce colonization and recurrent symptoms of vulvovaginal candidiasis, but routine primary prophylaxis with fluconazole is not recommended in women living with HIV.[96]

Gender-Based Violence and Women with HIV

Gender-based violence, defined as a woman’s experience of childhood or adult physical, sexual, or psychological abuse, increases a woman’s likelihood of engaging in sexual risk activities and substance use that may increase her risk of acquiring HIV.[99] If a woman acquires HIV and experiences the syndemic of gender-based violence (often intimate partner violence), this may place her at increased risk of developing mental health disorders.[99,100,101,102] Studies have found that 60 to 90% of women who are victims of gender-based violence develop anxiety disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder, and as many as 50% develop depression; these numbers are likely higher for women with HIV who already suffer higher rates of psychological disease at baseline.[103,104] Transgender women are also at significant risk of gender-based violence against them.[105,106] Clinicians caring for cis- and transgender women with HIV should be vigilant in screening for gender-based violence, as well as screening for accompanying mental health symptoms, given that depression and post-traumatic stress disorder decrease quality of life and have been linked to poor adherence with antiretroviral therapy and subsequent treatment failure.[107,108]

Menopause in Women with HIV

Age at Menopause

With the widespread availability of effective antiretroviral therapy, women with HIV are living longer, and more are reaching menopause.[109,110] Available data suggest that menopause occurs at an earlier age in women with HIV than in the general population; however, the results are confounded by many other factors that affect age at menopause.[109,110,111] In one multivariate analysis of data collected from a prospective cohort of 667 women with HIV, the presence of a CD4 count less than 50 cells/mm3 conferred a three-fold risk of early menopause.[109] Women with HIV also appear to experience a greater burden of menopausal symptoms compared with women without HIV.[111]

Effect of Menopause on HIV Acquisition and Transmission

There are concerns that age-related vaginal epithelial changes (such as atrophy and decreased mucosal integrity) might enhance the risk for HIV acquisition and transmission, in much the same way that mucosal ulcers disrupt the mucosal barrier and can enhance HIV susceptibility and shedding.[112,113] Despite these concerns, postmenopausal women with HIV have not been found to have increased genital HIV shedding compared with younger women.[113]

Antiretroviral Therapy in Peri- and Postmenopausal Women

Estrogen appears to have a protective effect on immune function, as evidenced by the fact that premenopausal women have higher CD4 counts and lower HIV RNA levels compared with age-matched men.[114] Despite concerns that postmenopausal women might have suboptimal immunologic and virologic responses to antiretroviral therapy as a result of decreasing estrogen levels, two studies have demonstrated equivalent responses to antiretroviral therapy regardless of menopausal status.[114] Unfortunately, given the higher rates of menopausal symptoms in women with HIV, there are limited data on the safety and efficacy of hormone replacement therapy in women with HIV, including limited information on drug interactions between hormonal therapies and antiretroviral medications.[111] Because current guidelines stress the need to weigh the risks and benefits of using hormone replacement therapy for the treatment of menopausal symptoms, women with HIV may not be ideal candidates for hormonal replacement therapy, given the increased rates of cardiovascular disease in the population living with HIV.[111,115]

Impact of Menopause on Other Conditions

Earlier onset of menopause requires heightened vigilance for conditions that are associated with postmenopausal status, such as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease, especially since HIV infection (and antiretroviral therapy, in some cases) may directly increase a woman’s risk of developing these disorders.[109,110,111,116] There are no HIV-specific surveillance recommendations for these conditions in women with HIV, but clinicians should emphasize the importance of age-appropriate screening and counsel about secondary prevention measures, including smoking cessation and regular exercise.

Summary Points

- In the United States, cisgender women and girls comprise an estimated 22% of all persons with HIV and approximately 19% of new HIV infections.

- Among cisgender women and girls in the United States with HIV, the identified factor for acquiring HIV was heterosexual contact in 80% and injection drug use in 20%.

- Black/African American and Latina women have disproportionately higher HIV prevalence and incidence rates.

- Women and men have similar virologic responses to antiretroviral therapy, though women are more likely to experience an increase in some antiretroviral-related adverse effects, such as loss in bone mineral density with tenofovir DF and ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors.

- For women with HIV who may become pregnant, the antiretroviral regimen should take into consideration what regimens are recommended for use during pregnancy.

- Women living with HIV should be offered the full array of contraceptive options and counseled about potential drug interactions with antiretroviral therapy.

- Multiple options exist for serodifferent couples seeking pregnancy. The strategies should be individualized, and the approach may differ based on which partner is living with HIV. The use of HIV PrEP has expanded these options.

- Women with HIV experience vaginal infections more often than women without HIV, and these infections can influence susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections and increase the risk of HIV transmission to uninfected partners.

- Menopause may be earlier and more symptomatic in women with HIV compared to women without HIV, but there is no data to support a link between menopause-related vaginal mucosal changes and an increased risk of HIV transmission to others.

- Women with HIV (both cisgender and transgender) experience high rates of gender-based violence, particularly intimate partner violence, and should be screened routinely as part of their comprehensive care.

Citations

- 1.UNAIDS/AIDSinfo. HIV and AIDS estimates: global factsheets 2017.[UN AIDS/AIDSinfo] -

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (Updated). HIV Surveillance Report, 2020; vol. 31:1-119. Published May 2020.[CDC] -

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV Incidence and Prevalence in the United States, 2014–2018. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2020;25(No. 1):1-77. Published May 2020.[CDC] -

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV Incidence and Prevalence in the United States, 2017–2021. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2023;28(3). Published May 2023.[CDC] -

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2021. HIV Surveillance Report, 2021; vol. 34. Published May 2023.[CDC] -

- 6.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Considerations for antiretroviral use in special patient populations: Women with HIV. September 12, 2024.[HIV.gov] -

- 7.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy. December 18, 2019.[HIV.gov] -

- 8.Collazos J, Asensi V, Cartón JA. Sex differences in the clinical, immunological and virological parameters of HIV-infected patients treated with HAART. AIDS. 2007;21:835-43.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 9.Currier J, Averitt Bridge D, Hagins D, et al. Sex-based outcomes of darunavir-ritonavir therapy: a single-group trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:349-57.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 10.Fardet L, Mary-Krause M, Heard I, Partisani M, Costagliola D. Influence of gender and HIV transmission group on initial highly active antiretroviral therapy prescription and treatment response. HIV Med. 2006;7:520-9.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 11.Rosin C, Elzi L, Thurnheer C, et al. Gender inequalities in the response to combination antiretroviral therapy over time: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. HIV Med. 2015;16:319-25.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 12.Gandhi M, Aweeka F, Greenblatt RM, Blaschke TF. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:499-523.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 13.Ofotokun I, Chuck SK, Hitti JE. Antiretroviral pharmacokinetic profile: a review of sex differences. Gend Med. 2007;4:106-19.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 14.Venuto CS, Mollan K, Ma Q, et al. Sex differences in atazanavir pharmacokinetics and associations with time to clinical events: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study A5202. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:3300-10.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 15.Brown TT, Moser C, Currier JS, et al. Changes in Bone Mineral Density After Initiation of Antiretroviral Treatment With Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine Plus Atazanavir/Ritonavir, Darunavir/Ritonavir, or Raltegravir. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1241-9.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 16.Grant PM, Kitch D, McComsey GA, et al. Low baseline CD4+ count is associated with greater bone mineral density loss after antiretroviral therapy initiation. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1483-8.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 17.Sharma A, Shi Q, Hoover DR, et al. Increased Fracture Incidence in Middle-Aged HIV-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Women: Updated Results From the Women's Interagency HIV Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70:54-61.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 18.Yin M, Dobkin J, Brudney K, et al. Bone mass and mineral metabolism in HIV+ postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1345-52.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 19.Sax PE, Erlandson KM, Lake JE, et al. Weight Gain Following Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy: Risk Factors in Randomized Comparative Clinical Trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:1379-89.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 20.Kerchberger AM, Sheth AN, Angert CD, et al. Weight Gain Associated With Integrase Stand Transfer Inhibitor Use in Women. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:593-600.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 21.Lake JE, Wu K, Bares SH, et al. Risk Factors for Weight Gain Following Switch to Integrase Inhibitor-Based Antiretroviral Therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:e471-e477.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 22.Venter WDF, Sokhela S, Simmons B, et al. Dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (ADVANCE): week 96 results from a randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV. 2020;7:e666-e676.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 23.Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Antepartum care for individuals with HIV. January 31, 2024.[HIV.gov] -

- 24.Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Antepartum Care. Recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy. Table 6. What to start: initial antiretroviral regimens during pregnancy for people who are antiretroviral-naive. January 31, 2024.[HIV.gov] -

- 25.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. What to start: initial combination regimens for people with HIV. September 12, 2024.[HIV.gov] -

- 26.Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Antepartum Care. Recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy: people with HIV who are taking antiretroviral therapy when they become pregnant. January 31, 2024.[HIV.gov] -

- 27.Zash R, Makhema J, Shapiro RL. Neural-Tube Defects with Dolutegravir Treatment from the Time of Conception. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:979-81.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 28.Zash R, Holmes LB, Diseko M, et al. Update on neural tube defects with antiretroviral exposure in the Tsepamo study, Botswana. Abstract PEBLB14. Presented at: IAS; 2021. Virtual Conference[PubMed Abstract] -

- 29.Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy: teratogenicity. January 31, 2024.[HIV.gov] -

- 30.Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy: pregnant people with HIV who have never received antiretroviral drugs (antiretroviral naive). January 31, 2024.[HIV.gov] -

- 31.Ford N, Calmy A, Mofenson L. Safety of efavirenz in the first trimester of pregnancy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2011; 25: 2301-4.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 32.Ford N, Mofenson L, Shubber Z, et al. Safety of efavirenz in the first trimester of pregnancy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2014;28 Suppl 2:S123-31.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 33.Zash R, Holmes L, Diseko M, et al. Neural-Tube Defects and Antiretroviral Treatment Regimens in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:827-40.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 34.Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Antepartum Care. Recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy. Table 7. Situation-specific recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant people and nonpregnant people who are trying to conceive. January 31, 2024.[HIV.gov] -

- 35.Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Appendix C: Antiretroviral counseling guide for health care providers. January 31, 2024.[HIV.gov] -

- 36.Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Protease Inhibitors. Darunavir January 31, 2023.[HIV.gov] -

- 37.Stek A, Best BM, Wang J, et al. Pharmacokinetics of Once Versus Twice Daily Darunavir in Pregnant HIV-Infected Women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70:33-41.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 38.Delany-Moretlwe S, Hughes JP, Bock P, et al. Cabotegravir for the prevention of HIV-1 in women: results from HPTN 084, a phase 3, randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2022;399:1779–89.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 39.Tepper NK, Curtis KM, Cox S, Whiteman MK. Update to U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016: Updated Recommendations for the Use of Contraception Among Women at High Risk for HIV Infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:405-10.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 40.Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Preconception counseling and care for persons of childbearing age with HIV. Reproductive options when one or both partners have HIV. January 31, 2023.[HIV.gov] -

- 41.Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.[MMWR] -

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update to CDC's U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010: revised recommendations for the use of hormonal contraception among women at high risk for HIV infection or infected with HIV. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:449-52.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 43.Tepper NK, Krashin JW, Curtis KM, Cox S, Whiteman MK. Update to CDC's U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016: Revised Recommendations for the Use of Hormonal Contraception Among Women at High Risk for HIV Infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:990-994.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 44.Wilkinson D, Ramjee G, Tholandi M, Rutherford G. Nonoxynol-9 for preventing vaginal acquisition of HIV infection by women from men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(4):CD003936.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 45.Tseng A, Hills-Nieminen C. Drug interactions between antiretrovirals and hormonal contraceptives. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9:559-72.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 46.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Drug-drug interactions. Table 24c. Drug interactions between nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and other drugs (including antiretroviral agents). May 26, 2023.[HIV.gov] -

- 47.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Drug-drug interactions. Table 24b. Drug interactions between non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and other drugs. September 1, 2022[HIV.gov] -

- 48.Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Preconception counseling and care for persons of childbearing age with HIV: overview. December 30, 2021.[HIV.gov] -

- 49.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Drug-drug interactions. Table 24a. Drug interactions between protease inhibitors and other drugs. September 1, 2022.[HIV.gov] -

- 50.Tittle V, Bull L, Boffito M, Nwokolo N. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interactions between antiretrovirals and oral contraceptives. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2015;54:23-34.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 51.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Drug-drug interactions. Table 24d. Drug interactions between integrase strand transfer inhibitors and other drugs. September 12, 2024.[HIV.gov] -

- 52.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Drug-drug interactions. Table 24e. Drug interactions between the CCR5 antagonist maraviroc and other drugs (including antiretroviral agents). May 26, 2023.[HIV.gov] -

- 53.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Drug-drug interactions: drug interactions between HIV-1 gp120-directed attachment inhibitors and other drugs (including antiretroviral agents) June 3, 2021.[HIV.gov] -

- 54.Comparison of female to male and male to female transmission of HIV in 563 stable couples. European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV. BMJ. 1992;304:809-13.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 55.Heffron R, Donnell D, Rees H, et al. Use of hormonal contraceptives and risk of HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:19-26.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 56.Blish CA, Baeten JM. Hormonal contraception and HIV-1 transmission. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65:302-7.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 57.Polis CB, Phillips SJ, Curtis KM. Hormonal contraceptive use and female-to-male HIV transmission: a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. AIDS. 2013;27:493-505.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 58.Tepper NK, Curtis KM, Nanda K, Jamieson DJ. Safety of intrauterine devices among women with HIV: a systematic review. Contraception. 2016;94:713-724.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 59.Stringer EM, Giganti M, Carter RJ, El-Sadr W, Abrams EJ, Stringer JS. Hormonal contraception and HIV disease progression: a multicountry cohort analysis of the MTCT-Plus Initiative. AIDS. 2009;23 Suppl 1:S69-77.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 60.Stringer EM, Levy J, Sinkala M, et al. HIV disease progression by hormonal contraceptive method: secondary analysis of a randomized trial. AIDS. 2009;23:1377-82.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 61.Phillips SJ, Curtis KM, Polis CB. Effect of hormonal contraceptive methods on HIV disease progression: a systematic review. AIDS. 2013;27:787-94.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 62.Heffron R, Mugo N, Ngure K, et al. Hormonal contraceptive use and risk of HIV-1 disease progression. AIDS. 2013;27:261-7.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 63.Heikinheimo O, Lehtovirta P, Aho I, Ristola M, Paavonen J. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in human immunodeficiency virus–infected women: a 5-year follow-up study. AJOG. 2011;204(2):126.e1-4.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 64.Ralph LJ, McCoy SI, Shiu K, Padian NS. Hormonal contraceptive use and women's risk of HIV acquisition: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:181-9.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 65.Polis CB, Curtis KM. Use of hormonal contraceptives and HIV acquisition in women: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:797-808.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 66.Polis CB, Curtis KM, Hannaford PC, et al. An updated systematic review of epidemiological evidence on hormonal contraceptive methods and HIV acquisition in women. AIDS. 2016;30:2665-2683.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 67.Noguchi LM, Richardson BA, Baeten JM, et al. Risk of HIV-1 acquisition among women who use diff erent types of injectable progestin contraception in South Africa: a prospective cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2015;2:e279-87.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 68.Delvaux T, Buvé A. Hormonal contraception and HIV acquisition - what is the evidence? What are the policy and operational implications? Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2013;18:15-26.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 69.Colvin CJ, Harrison A. Broadening the debate over HIV and hormonal contraception. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:135-6.[PubMed Abstract] -

- 70.McCoy SI, Zheng W, Montgomery ET, et al. Oral and injectable contraception use and risk of HIV acquisition among women in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2013;27:1001-9.[PubMed Abstract] -